Cows gone astray

Lush meadows, three cows: Anna, Isabel and Ursina. They were not especially philopatric, so I had no other choice but to fence them in. I purchased wooden posts and a special red wire – actually, tinsel wire would be the correct term, explained the salesperson – as well as a cattle guard, the electrical unit that makes sure the wire nips cows and humans. No sooner were the cows enclosed in their paddock when the neighbours began bringing me stale bread. For the cows, they said.

I fed them by the basketful. The animals seemed to be contented with this variation. But then again, feeding on grass alone, who fancies that?

One morning, when I wanted to check on the cows and deliver the bread as usual, the paddock was empty. Everything was absolutely still, no twittering of birds, no chirping of crickets, nothing. Just the ticking of the cattle guard. For days on end, I searched for Anna, Isabel and Ursina. The entire village even helped, to no avail. The cows had gone astray. Occasionally, we found imprints of their hooves; we even spotted a cowpat. It was still warm. But after that the trail was lost.

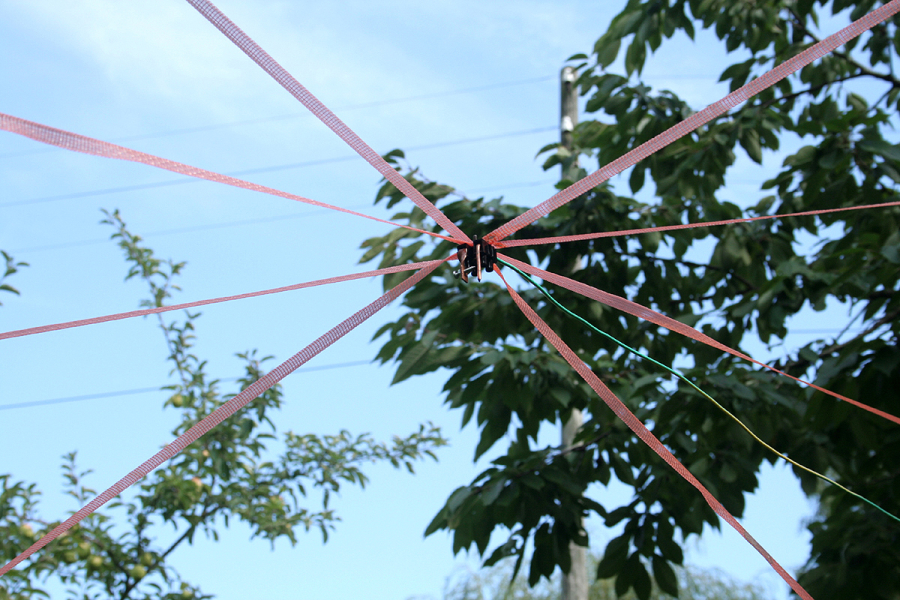

Dolefully, I returned to the paddock for the last time. It had changed completely. The fence was no longer a square. Now the posts were arranged in two lines so that they crisscrossed to form a rectangle with four sides of varying lengths. In front of the intersection point stood two posts on top of each other. It looked like the frame of a cube with four gates. Tentatively, I walked through one of them. Tick, tick, tick. I heard the cattle guard, but could not see it. My hair stood on end. Sparks flew, above me it crackled and buzzed. I looked up. Hovering in the sky was a house of cards made of slices of dry, stale bread.

As if out of my mind, I ran home and collapsed into bed burning hot. After many weeks, when the fever finally subsided and I regained consciousness, I decided to become an artist and hang up my previous life as a housewife. My career was swift and spectacular. I worked in New York, Paris and Hong Kong, constantly assisted by an extensive staff. Obama, the Dalai Lama and Madonna invited me to receptions; Vogue, Vanity Fair and Forbes featured me on their cover; the Tate, the Guggenheim and the Centre Pompidou honoured me with comprehensive retrospectives. I was rolling in money.

Decades had passed before I returned to my village. In the meantime the paddock had become a pilgrimage site. Thousands flocked to it every day, waiting in long queues to stand in the centre of the cube for a few moments. It sparked, crackled and buzzed. And above this all, the house of cards made of slices of dry, stale bread, with the cattle guard still ticking. I remained only briefly and never returned.

Suzann-Viola Renninger

Sharon Kroska e